Living Greener: How I learned to forge a a knife and the importance of traditional skills

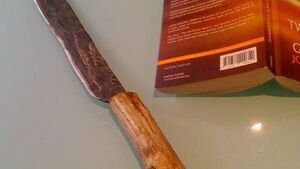

The handcrafted knife made by Brian

IF you ever want to have a great time learning traditional skills, the best place to go is the organisation CELT, which hosts weekend courses at Slieve Aughty in County Galway.

Their courses include furniture-making, basket-weaving, leather-working, stone building, longbow carving and many other crafts, and the last time we were there – while my daughter learned to sculpt a pizza oven out of clay — I learned to forge a knife.

Medieval people regarded smiths as they did alchemists, people who could transfigure bits of the world into something else, and doing it feels a bit magical.

Under the guidance of two experts, I took a rusty piece of spring thick as a finger – a piece of an old industrial machinery – and heated it until yellow and glowing, and bit by bit, hammered it into shape.

We started by creating a forge – in this case, out of clay, sand and horse manure, mixed and shaped like a sandcastle.

We also cut and stapled plastic fertiliser bags and wooden planks to form our own makeshift bellows and used pipes to connect them to the forge.

Into the middle of the forge, we placed charcoal, which burns much hotter than wood. Iron-working only appeared in the last 5,000 years or so – the final 0.3 per cent of the time humans have had fire – and only then could the Bronze Age become the Iron Age.

Also useful are steel vices and hefty pliers, which allowed us to grip metal while turning it – hence the twist in the fork handle. None of us wore gloves, but leather aprons and goggles were recommended against flying sparks and coals.

In movies, blacksmiths look like WWF wrestlers, dramatically slamming white-hot metal with sledgehammers. In reality, there’s a lot more tapping furiously with small hammers and a lot of waiting for it to heat up. Too little heat, of course, and the metal cannot be worked, but too much and it begins to “burn,” liquefying and deforming.

Once the metal was glowing orange, we had to rapidly move it to the anvil without yanking it out and sending hot coals everywhere, burning the people standing shoulder-to-shoulder with you! Once at the anvil you had only several seconds of BAMBAMBAMBAMBAMBAM ... until it was black and solid again.

In this case, I hammered the old machine part into a straight bar, flattened it into a knife-shape over the next two days, and a bit of cutting and polishing did the rest. I cut a handle from a hazel branch, heated the “handle end” of the metal until it was yellow-hot, and seared the hot metal into the handle, with a gust of steam and a few bursts of flame from the wood.

The end result didn’t look like something you’d buy at a cutlery shop, but it was shaped metal, and one side could be sharpened until it looked like an orc blade from Lord of the Rings. It was much cooler than getting one from a shop.

Blacksmithing is one of the dozens of professions that were widespread until just the last century, now is kept alive only by a few aficionados. For thousands of years in metalworking cultures, smiths were a vital and respected role – look how common it is as a surname today.

We should start to appreciate them again — with charcoal and tools, a smith could turn landfill scrap and old car parts into useful tools again — and as far as I know, there is no end to the number of times metal can be recycled.

Specialist trades like this are important, for at some point there will be no more coal and oil we could use to run industrial forges or make plastic goods.

Old plastic can only be recycled so many times until it becomes unusable. What we will have decades from now, however, is mountains of landfill waste, including scrap iron.

Movies like WALL-E posit garbage covering the Earth, but in real life much of that garbage would not only be reusable, but precious. It would be filled with metal that we can detect and re-forge, if we know how, and today’s landfills could be tomorrow’s mines.

For more information about CELT’s Weekend in the Hills, check them out at http://www.celtnet.org.