Living Greener: The beauty of 'Father Christmas'

Father Christmas by Raymond Briggs

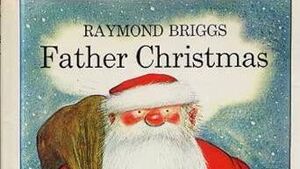

THIS time of year, my daughter has one favourite story: Raymond Briggs’s , the story of Santa’s rounds on Christmas night. It’s one of my favourites as well, if for different reasons.

In this graphic novel, silent but for a few grumbles and greetings, there is no Mrs Claus, elves or secret toy-industrial complex.

Father Christmas, here, is an old man living in apparently contented solitude, dutifully venturing out yearly to make his deliveries.

He endures storms, fog, sleet and high winds across the world, complaining the entire way and occasionally strengthening his resolve with a drop of liquor.

Such an unsentimental portrait might sound depressing, but it makes Santa more human and more comprehensible to my daughter, than the usual laughing caricature.

Briggs makes him a working-class man performing a service we value; Briggs could easily be showing the daily routine of a miner, a fisherman or a farmer.

At one point Santa passes a milkman also making deliveries, and they exchange pleasantries without stopping – and even on Christmas morning, the milkman must make his rounds as well.

What I particularly like, though, is that Santa seems to live on a homestead. He starts his morning by using the outhouse — at least, it’s a toilet outside in the shed — and gathers hay for the animals.

He is pleased to find two winter eggs from the chickens, and has breakfast with tea. He stokes the small stove, similar to the one we use to burn our bog turf.

You wouldn’t be surprised to see a vegetable garden or greenhouses out back. It looks like the working-class life G.K. Chesterton or C.S. Lewis might have recognised, the life an old man might have lived in Britain when the book was written in 1973.

It dotes on the minutiae familiar to hundreds of generations of Irish, an austere but civilised world that we might be able to revive, as an alternative to worse futures.

In a small room, Father Christmas sleeps under quilts, in long johns, with a hot-water bottle, for heat was precious. The bed-stand looks of rough wood, as though he carved it himself, and on it he keeps his teeth and a wind-up alarm clock.

The concept of a carbon footprint was decades away when the book was written, but without adding anything for flying reindeer, Santa’s would be close to zero.

As he makes his rounds, we see farmhouses by moonlight, and my six-year-old points out the details she recognises — bicycles, water barrels to catch rain from gutters, sticks crossed in the garden for peas to climb. Sometimes Santa has to crawl out of the stove, for people cooked with wood or coal and the oven went to the chimney.

The whole story, of course, made more sense when it was gaining popularity in the 19th and early 20th centuries; most children were familiar with sleighs or lumps of coal, and hung their stockings by the chimney anyway, to dry.

In , Mama was in her kerchief and I in my cap because the houses were cold. Children a century ago would not have found such verses cryptic, any more than they would stables and mangers.

Today, it might seem like that world has been completely forgotten. As we inched into decadence and debt, Ireland abandoned most of its traditional holidays – Wren Day, Midsummer, Bridget’s Day, Lughnasa, May Day and many more – and swelled Christmas from a night to a shopping ‘season’.

Christmas movies and television increasingly portrays Santa’s workshop as an assembly line, while news pundits annually track the spending numbers like telethon hosts.

Yet people can’t completely forget a more traditional world this time of year, not amid so many traditions.

It is at this time of year that modern people are most likely to visit family, cook their own food, meet their neighbours, go to their parish church, bring greenery inside, go from house to house caroling, or even watch black-and-white movies from a short time ago, when we had less of what we wanted and more of what we needed.

When we take pleasure in these things, we peek through cracks in the world of screens designed us to distract us and see another, older country on the other side, and realise that is the real source of comfort and joy.